Jim Andris, Facebook

Gay Academic Union—St. Louis

Brief History of the National Gay Academic Union

The Gay Academic Union emerged from the years of ferment in the early 1970s following the explosion of gay rage at Stonewall on June 28, 1969. One of the many ways that awareness of social wrongs to the gay community and gay awareness itself gushed up in those early days was in the form of hundreds of gay student groups on campuses around the nation, following on the heels of early gay activist organizations, such as the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. The energy of the student protests for civil rights and against the Vietnam war was still palpable; students were still in a protesting mood. In 1973, in a Manhattan apartment, eight gay academics met and began to discuss problems of doing research. John D'Emilio was one of them, and he has written an account of that first year of meetings and subsequent conference.

The Gay Academic Union was always first and foremost an organization for and about working, writing, and living in an academic environment. According to D'Emilio's account, after the first year of struggle with core issues, it was an organization dedicated to parity of representation of both lesbian concerns and those of gay men. The Gay Academic Union Statement of Purpose (1973) contained this list.

"The work of gay liberation in the scholarly and teaching community centers around five tasks which we now undertake:

- to oppose all forms of discrimination against all women within academia.

- to oppose all forms of discrimination against gay people within academia.

- to support individual academics in the process of coming out.

- to promote new approaches to the study of the gay experience.

- to encourage the teaching of gay studies throughout the American educational system."

It is worth quoting this paragraph of the Rainbow History account as a concise overview of the history of GAU at the national level.

"The Gay Academic Union both celebrated the gay experience in higher education and advocated for the rights of LGBT academics within tertiary institutions. It also advocated for the inclusion of gay studies in academic course offerings. Conferences continued into the next decade, growing in size and diversity of topics. By the late 1970s, gay and lesbian caucuses had begun forming within the professional associations of academic disciplines: the Association of Lesbian and Gay Psychiatrists organized in 1978, the Anthropology Research Group on Homosexuality in 1978, the Committee on Lesbian and Gay History in the AHA in 1979, and more formed in the 1980s. Throughout the 1970s, regional and local Gay Academic Unions spread across the country as local academics confronted issues within and across their disciplines. Chicago's Gay Academic Union participated in the founding of the city's Gerber-Hart library and archives."

As we shall see, the St. Louis Chapter of the Gay Academic Union, as it existed in 1979-1980 was not cast in this mold.

The Establishment of a Gay Hotline through MLSC

Rev. Carol Cureton founded the Metropolitan Community Church in 1973 and successfully gathered a large following in the subsequent two years. In late 1974, MCC St. Louis moved to a large building at 5108 Waterman in the Central West End. The following year, in mid-1975, a secular offshoot of MCC was formed with the church's blessing and continued to meet for a while in the church building. The organization was called the Metropolitan Life Services Center (MLSC), a name that had been given much careful thought. Even though there was no indication in the name itself, it was to be a gay life services center. In the mid 1970's the prevailing opinion among the gay leadership in St. Louis was that caution was required. The word "metropolitan" served both to solidify the connection between the organization and MCC and also to emphasize service to the metropolitan area. Later, Met Life would sue the organization, necessitating its renaming to the MidContinent Life Services Center.

During the next three years (1976-1978), MLSC published in its newsletter, PrimeTime, local and national events of interest to the gay community. Responding to the fact that "at the time St. Louis was the largest city in the country without a GLBT hotline for information, referrals and crisis intervention," (Lesbian and Gay Memorials, 2005) the first St. Louis Gay Hotline was soon established, and answered an average of 188 calls a day. The community responded so positively that MLSC moved to its own building on McPherson Avenue for a time and founded what was essentially a community center with a broad range of services and activites. However, funding challenges for the larger space and operation, the usual disagreements and disputes and the fact that 1977 was a turning point year for community fortunes (the hate campaign from Save the Children), the Center first moved to a smaller space at 10 N. Euclid and then closed its doors towards the end of 1978.

Galen Moon is usually given credit for being a, if not the, founding father of MLSC. Born in 1902, Galen had lived a long and colorful life, much of it dedicated to service to the gay and lesbian community. He was certainly a principle mover throughout the tenure of the Center and remained engaged in forming the Gay Academic Union—St. Louis Chapter as a new not-for-profit home for the Gay Hotline. Bill Cordes (1945-2005), young and newly come out in 1977, also brought considerable skills and energy to this project. He brought publishing interest and skills and a dedication to the Gay Hotline, becoming the first Chairperson of the Hotline Committee of the Gay Academic Union, once it was formed. Bill would go on to still other major projects, notably, helping to found St. Louis' gay and lesbian youth organization, Growing American Youth, and starting Gay Life magazing, both in 1979, and opening the bookstore Our World Too in 1987. Other people dedicated much time and energy to the Center, notably Ray Lake with social and political issues and the hotline.

Formation of the Gay Academic Union—St. Louis

There are strong indications that Galen Moon and others had a plan for preserving the Gay Hotline and perhaps some of the other activities and services of MLSC. Galen had read about the growth of the national Gay Academic Union and its outreach to form new local and regional chapters. Working with a nationally known and published former St. Louis resident, Betty Barzon—also President of the National Board of Directors of GAU—Galen engineered the creation of the St. Louis Chapter of GAU in late 1979, just on the heels of the closing doors of MLSC.

The National GAU had been formed in 1973 as an organization dedicated to the specific needs of gay and lesbian academic professionals: discrimination, coming out and gay studies. It was not the best fit as a legitimate shelter for the Gay Hotline, and Galen probably knew that. A letter on official National GAU stationery dated Nov. 11, 1978 soliciting membership in the newly forming organization and sent to over a hundred potential members contained an attachment titled "10 Questions and Answers." Question 4 was "Why do we need a tie-in with a national organization?" Galen gave four reasons why and in this order: tax-exempt status, tax deductable contributions, prestige, experience and clout of a national organization, and finally, encouraging a range of academic activities, unbiased research, publication and presentation of gay scholarly papers, gay art, and teaching gay studies. And, as a matter of fact, the first and third president of the St. Louis organization did plan and support some academic activity for the organization.

By the end of 1978 Galen was able to report to a membership of 28 that GAU-St. Louis had received its official tax-exempt status and that a number of donations and offers of help and support had been received from the membership. For the first time, talk about the Hotline is introduced: the membership will be asked to consider allocation of a small percentage of membership fees to the Hotline and the creation of an account for Hotline pledges. A meeting on Jan. 12 was scheduled to consider adoption of a constitution and by-laws, which were based on a national model, but tailored to St. Louis' specific needs. Galen also reported that he had been elected to the GAU National Board of Directors at the Nov., 1978 national meeting.

A memo from the Interim Steering Committee to (now 37) GAU-SL members on Jan. 21, 1979 reported that a final copy of by-laws and constitution had been developed for approval at the Feb. 2 meeting. Following approval of these, nominations and election of officers could proceed. It is reported that the MCC Board of Directors agreed to allow GAU-SL to meet in their building at 5108 Waterman. An Interim Hotline Committee composed of Bill Cordes, Wayne Huber and Craig P. reported on efforts to reinstall and house a Hotline Phone. A copy of an agenda for the Feb. 2 meeting shows that the bylaws and constitution were indeed adopted and indicate that Moon, Cordes, Huber and Ray Lake were reporting on various tasks.

A March 28, 1979 letter to Wayne Huber from Galen Moon congratulates Wayne on "the result of the GAU-SL elections. Congratulations! I'm sure you will do much to make the organization both productive and respectable in the metropolitan area." He offers a couple of suggested names of people who would work hard on various projects. It seems clear that Galen has moved to Chino, California at this point. The Gay Academic Union participated in or supported the 1979 Gay and Lesbian Pride activites held at Washington University Apr. 20-22, according to the brochure. Wayne Huber may remember more about this crucial period in the history of GAU-SL.

Some time between March, 1979, and March, 1980, a man named Ken Dayringer replaced Wayne Huber as the head officer of the Gay Academic Union. Both the Magnolia Committee and the Celebration Committee would have been planning the 1980 Pride activities since early that year. It's not clear what positive contributions Ken may have made to GAU-SL, but the negative consequences of his officership in the organizations were dire. Ken had been running a call boy service from his home, and the police found out about it and raided his domicile, confiscating, among other things, the address box of names and addresses of members of GAU-SL that Ken received upon assuming office. People were literally terrified that they would suffer police retribution.

Eventually, this incident made it into the national gay newspaper, The Advocate.

St. Louis gay activist Kenneth Dayringer was arrested May 8 [1980] on charges of prostitution and promoting prostitution. Bond was set at $250,000. Dayringer, former chair of the St. Louis chapter of the Gay Academic Union, is operator of the Wan-A-Man Escort Service. A real estate agent who saw a picture of a naked man while appraising Dayringer's house tipped off the police. There was concern in the St. Louis gay community that Dayringer's arrest indicated an increase in antihomosexual activities by the vice squad.

Jim Andris, a professor of education at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, and also an out gay activist on his campus and in the metropolitan area, was approached to assume the presidency of the organization. There weren't many with academic credentials who would even consider such an offer. But Jim did, and even drove out to visit Ken Dayringer at his home. While two young, tattooed male prostitutes hovered in the room (Ken said at one point, "Now be good, boys.), Jim discussed the situation with Ken and retrieved the metal box of names that the police had returned. Ken indicated that he was going to be tried for pandering. As a result of the legal proceedings against Ken, he was convicted of running a male prostitution service and spent three years on probation, starting in June, 1981. This event was again reported in the Advocate.

Jim Andris wrote in his 1981 Christmas Letter:

"I completed a year as Chairperson of the Gay Academic Union in March, and felt very much like I had helped the organization to get back on its feet. We had socials, a picnic in June, and even Masters and Johnson spoke with us. We're still not without our problems, but I'm on a task force now to iron these out." from Jim Andris' 1981 Christmas letter.

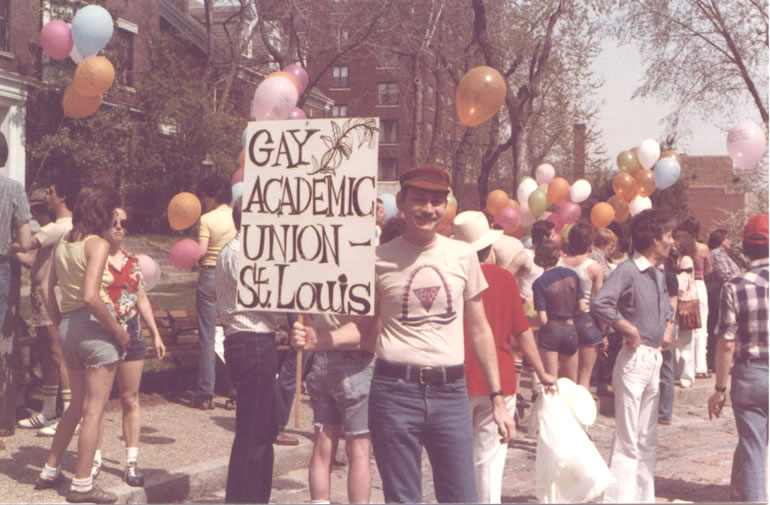

Jim recalls that the Masters and Johnson meeting with GAU was held in a huge mansion on Hortense Place just off Euclid, the home of one of the members. About 30 people were in attendance. Below is a picture of Jim Andris carrying a Gay Academic Union–St. Louis sign drawn by Wayne Huber. The picture was taken by Jon Schneider, who, along with Ray Lake, were joining Jim in the Walk for Charity.

Jim Andris wrote in the late 1980s a reflection called "A Crisis at the Gay Academic Union." Here are excerpts from it.

In March of 1980 I became the chairperson of GAU. I was working hand in hand with a crew of seasoned gay rights activists: Bill Cordes, Lisa Wagaman and Ray Lake, all of whom had helped to start the Gay Hotline several years before. There were very few academicians in this organization. There were a few, though, who shall remain nameless, since their jobs in education are at stake. You may recall that I was put in place of Ken Dayringer, convicted of pandering and arguably responsible for a list of names of GAU members falling into the hands of local police.

I supported the Hotline, but I was not active in it. That was an operation onto itself. Classes of new volunteers went through training on how to deal with confidential calls and crisis situations, such as impending suicides. This was just the kind of thing that attracted some of the younger members of the community. Working on the Hotline was doing something specific to help someone, by contrast to a bunch of academics sitting around and talking about gay rights. As I explained before, the GAU in St. Louis, unlike some of its east and west coast counterparts, had been mainly a front for the Hotline in order to gain tax-exempt, not-for-profit status. From my point of view at the time, however, there was precious little academic about the Gay Academic Union in St. Louis.

I set about to arrange to have more topic-oriented meetings. In fact, many of the successful ideas that we had that year—an open picnic in Tower Grove and a talk by Masters and Johnson at the Central West End home of one of the members— were the brainchildren of Wayne Huber, a local person well know in art and educational circles. As the year wore on, the Hotline crew, mainly under the leadership of one Donn Kleinschmidt, became very displeased with this academic focus. What I got was that they wanted the GAU to become almost a service organization dedicated to supporting the hotline. There was even some not so subtle ageism in some of the criticisms that came our way, "the older crowd" was an epitaph that was hurled more than once. Ultimately, this state of antagonism lead to my resigning from the chair.

While time has dimmed my recall of the precise exchanges that took place between the two sides vying for control of GAU, there is a part of one event that stands out in my mind. My friend and former student, Kathy had warned me that Donn was set to try to move control of GAU to people who were more specifically focused on the needs of the Hotline. I found out later that Donn had impressed Kathy with his arguments, and that she was herself of divided opinion about the proper direction and balance of GAU St. Louis.

A meeting was scheduled, I think, at MCC at its then location of 5108 Waterman. About 15 people were present, but the real confrontation came down to Donn and me. He had come quite fully prepared for a knockdown, drag-out argument over the direction of the organization. However, after listening and discussing for a short time, I simply said something to this effect: “Well, look, I was drafted to do this job because no other “out” academic was willing to do it. I have done my best, brought the organization through one crisis (with Ken Dayringer), and I do have a certain vision for the organization. But if someone else (meaning Donn) thinks they can do a better job, by all means, have at it!” I clearly remember that shortly after I had made this statement, Donn, said, in effect, “Why am I always made out to be the villain?” And he threw a coke can across the room in anger. But whatever, the leadership transferred hands, and I was glad to have less to worry about.

This story is an important inclusion into the historical record. When Jim Thomas was interviewed by Lisa Kohn in 2003, he indicated that he initially gravitated towards the Gay Academic Union when he returned to St. Louis in late 1979. He gives a fairly accurate overview of the history of the hotline, but this article should clarify some things about the nature of the Gay Academic Union here:

Well, they [GAU-SL] were primarily a group of people connected in somehow with teaching at Washington University. And to be honest with you, I’m not really sure, in today’s language I think what I would say is they were probably all kind of adjunct professors. I think Washington University was a more conservative community than Oberlin was, and probably, I don’t know, the tenured professors would have more protection. But I think they also perceived they had something to lose in the way of reputation. Its primary activity at that point was the hotline. There had been a group earlier called, initially, Metropolitan Life Services Corporation, and then Metropolitan Life Insurance threatened to sue them, so they became Midcontinent Life Services Corporation so that they could keep the same name, or same initials rather. It ran the hotline, and they imploded over some internal whatever, I was not involved in it, so I certainly heard things but can’t speak to them firsthand. They had actually had a physical property as a community center, and that was all lost. It was down on McPherson, between Euclid and Kingshighway. But the one thing that was salvaged out of that was the hotline, and the Gay Academic Union ran that for a short time. And then there was a group of people who were either professional or student, sort of therapist/psychology types, who decided to split off and run the hotline independently. Gay Academic Union lost its main tangible project at that point and pretty quickly faded. I don’t remember when it actually died, but without that to do, it lost impetus.

Editor's note: In retrospect, I can see that the Gay Academic Union St. Louis never really existed in any full sense. Galen Moon engineered the whole thing, and then left the area. Jim Thomas' observation about the closeted nature of academics was probably descriptive of some of the people he met, certainly not of me. And certainly not of some of the individuals that were in the Women's Studies program and Washington University. I don't recall that any of them ever came to these fledgling meetings of GAU-SL. In retrospect, had I somehow had the information or insight to link up with them at the time, the organization might have had a better chance of surviving in an authentic way, while still maintaining support for the Gay Hotline.

References

Cordes, Bill (1945-2005), Lesbian and Gay Memorials, http://memorials.gayandlesbianmemorials.com/2005/02/23/cordes-bill-19452005.aspx

Resources on the Gay Academic Union, http://www.rainbowhistory.org/gau.htm This is an extensive online collection maintained by The Rainbow History Project. It contains proceedings for the 1973-1976 GAU National Conferences as well as a brief history and over and related links.

St. Louis Activist Is Jailed for Prostitution, Advocate, 6/26/1980, Issue 295, p. 9; Short takes, Advocate, 6/11/1981, Issue 319, p. 53.

Wilson, Rodney C. "The Seed Time of Gay Rights: Rev. Carol Cureton, the Metropolitan Community Church and Gay St. Louis, 1969-1980." Gateway Heritage, Fall 1994, pp. 34-47.