Jim Andris, Facebook

St. Louis Organizing Committee/St. Louis Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights (SLOC/IRIS)

The first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights was held on October, 14, 1979. Efforts to mobilize such a March on Washington had been started and stalled twice before in 1973 and 1978. St. Louis was well-represented at this event. It is likely that this would not have been the case, were it not for the organizing political activity of the young Jim Thomas.

Thomas entered Oberlin College in the Fall of 1975. He debated over Oberlin College and Lawrence University, but finally chose Oberlin because it had a gay student organization listed in the college catalog. He quickly became involved with that organization. During the summers, Thomas came back to his home in Alton, Illinois, and as he found it rather lonely in that community, he explored and connected with gay organizations in St. Louis, particularly the Metropolitan (later Midcontinent) Life Services Center (MLSC) and, later than that, the Gay Academic Union (GAU). In the summer of 1977, during the Anita Bryant terror campaign, Thomas and Rick Garcia were interviewed by the St. Louis Post Dispatch. In the wake of the assassination of Harvey Milk in November of 1978, a renewed effort was made to organize a National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

Jim Thomas was a senior at Oberlin College when he went with a group of "Obies" to attend a conference in Philadelphia on Feb. 23-25, 1979, the purpose of which was to determine the structure and platform for a National March. Noting that California, the East Coast, and the Northeast Coast were dominating those proceedings, Thomas "in my usual way, spoke up and said, 'Well, you know, there’s some of us who aren’t in those places, and you need to include us.'

"And so out of that … maybe it was Paul Boneberg [who] was one of the people who worked on that march—He was from San Francisco—who asked me to do some organizing, … starting out in Southern Illinois and Eastern Missouri, and then it ended up … growing to include like, Iowa, I think I did something in Indiana, but it was primarily Missouri and Illinois outside of Chicago where I worked, and I would go to meetings of groups, I would ask to appear and talk about the March, try to get people interested in attending. Had a big meeting in Springfield, Illinois. I remember going over to Kansas City, and there were people there. I went and met with Lea Hopkins [inaudible]. And of course, St. Louis. And so, there really was a very direct trail at that point from my doing that organizing work to the March to beginning to know and work with people in the St. Louis community at that time, which had evolved some, because of the collapse of Midcontinent Life Services. (Interview of Jim Thomas.)

Jim also recalls braving a horrendous snow storm on the Pennsylvania Turnpike as the selected driver for the return trip from Philadelphia back to the college. Part of the commission of this group of "Obies" was to hold a Midwest organizational meeting at Oberlin in the second quarter of that year.

Jane Levin was to become another regional organizer of the National March on Washington in 1979. She came to St. Louis in 1973 to begin studies at Washington University and "became somewhat active in the lesbian community soon after that." Amid all the organizational work that Jim Thomas did for the Midwest in the 1979 winter and spring, flyers soliciting support for a National March on Washington were put up at Midwest sites. Jane saw one of these flyers in the Central West End of St. Louis, and called the displayed 800 number.

"So I call up, they tell me that Jim Thomas, they give me his phone number. I call him up, he says, yeah, yeah, that’s me. He and I get together, we started talking, and we decide we’re going to organize our part of the country for the March on Washington. … So he and I began making flyers, trying to contact people, putting out flyers at the bookstore, the Sunshine Inn, I started putting them out in the lesbian community, talking to people." (Interview with Jane Levin)

Levin describes her experience of the organizational meeting held at Oberlin College.

five women crammed into a little bitty car, and we drove to Oberlin. We slept on the floor of a dormitory room and attended this meeting, which was, in my recollection, a yelling fest. I mean, you know, there were so many agendas going on, there were women, there were people of color, there were, there were all kinds of economic issues. … But we did hammer out a list of demands that we wanted, and we went back and we started fund-raising so that we could help send some people to the March. I don’t think we were particularly successful, but we did subsidize a few people to go. (Interview with Jane Levin, email from Jim Thomas.)

Jim Thomas had similar memories. In particular, they were both impressed by a man name Eric Rofes.

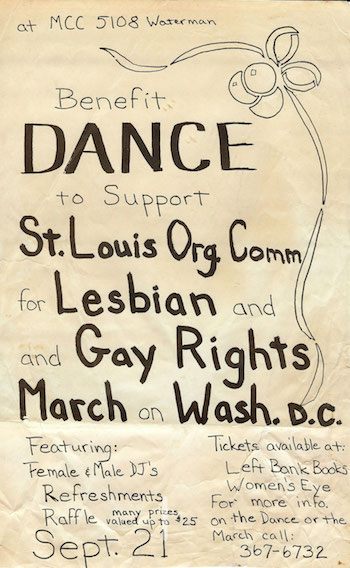

|

| Poster contributed by Jim Pfaff. |

Later, but still some time before the actual event in October, Levin remembers that Jim called her one day and said

“There’s gonna be a meeting,”—I think he called it a ‘White House meeting', but I don’t think it was at the White House—“and they want a representative from the Midwest, and since there’s gender parity, it needs to be you.”… And I didn’t, I felt like it should have been Jim, I thought that, Jim had done more to organize this, was more involved, and really deserves to represent the Midwest, but couldn’t because he’s a man. … So I agreed to do that.

In an email to the author Thomas discusses the gender parity issue in detail. Early in the March planning, the decision had been made to have equal representation for men and women and 25% people of color.

The whole point of such quotas [is] to ensure that organizations find ways to be more inclusive and give marginalized groups a real and meaningful voice. But in the context of organizing very, very rapidly, there was no time for these organizations to find people who could represent and do the work for their regions. This wasn’t just a matter of finding a Black woman or a Latino man. It involved the ability to be out of the closet for such a role and the willingness to make such a commitment to the work. The end result was a vast over-representation of coastal communities in the numbers, style and political content of organizing, with portions of the country having no representation at all because regions that didn’t make the quotas were excluded from participating. In the end, I think the only way the March actually happened successfully in October, was that there was a separate group working on all the logistics and such who just kept their noses to the grindstone and carried on regardless of whatever was happening in the political overlay that would be represented by things like who was going to speak at the rally, the nature of entertainment at the rally and demands.

Now, there had been a very significant event on March 26, 1977, which has been documented by Clendinen and Nagourney (Out for Good, Ch. 21.) Midge Costanza, a New York State politician who campaigned for Jimmy Carter, had been appointed assistant for public liason to the Carter Administration. Strongly advised by Jean O'Leary and Bruce Voeller of the National Gay Task Force, Costanza had arranged a meeting in the Roosevelt Room with seven women and seven men representing the lesbian and gay male community of the time (with notable absences). For three hours O'Leary, Voeller, Charlie Brydon, Charlotte Bunch, Ray Hartman, Elaine Noble, Troy Perry, Betty Powell, Franklin Kameny and five others told their stories to Costanza and two other government officials.

Carter had no knowledge of this meeting. While Carter had strong humanistic leanings, he made no commitments to either the gay and lesbian community or the strong Christian fundamentalist lobby of the time, disappointing both. Further, Costanza became more and more impatient with the situation and resigned from the position in August, 1978. There is evidence that the liason between the Carter Administration and the gay and lesbian community continued, however: "A twenty-person delegation from the [1979] March met at the White House with Jane Wales, a holdover from Midge Costanza's staff who had become a low-level aide to Anne Wexler, Costanza's replacement." (Clendinen, op. cit., p. 408)

It is highly probable that Levin was at this 1979 meeting:

I sat next to a couple of representatives from the Carter Administration, on their left. It was a big, oblong table, or rectangular table. And I thought, “Good, I’ll be the last one to speak.” And there was some undersecretary of housing there, and I can’t remember who else was represented by the Carter Administration, but they turned to me and said, “Let’s start with you.” And I was totally unprepared, and I said, “Well, I’m Jane Levin, I’m from Saint Louis,”—and I’m embarrassed to say this now cause I’ve lived in the Midwest since I was twenty three—but, I said, “We’re not all farmers.” [Laughter.] And somebody from the Carter Administration said, “Well, that’s ok, you know, we need farmers.” And then I told them about a lesbian couple in Madison who had been denied housing because they were a lesbian couple, and I knew, I had the details of who they were and where they lived and all of that, and this woman says, “Really?!” from the Carter Administration, and I said, “Yes, and what are you going to do about it?” … She said, “Well, we will look into that.” And then we went around the room and each person said their piece about what was important to them, and then we were starting to wrap up. And I turned to this woman again, and I said, “Will you follow up with me on this?” and she said, “Oh, yes.” Well, as you might imagine, I never heard from her. … And that was a really historic meeting, I think, and I was very proud to represent the Midwest and very scared.

In fact a sizeable contingent from St. Louis attended the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979, maybe as many as 30 people, but some of them traveled independently of this organizational effort. The Wikipedia article on the March is actually a good entry point into understanding this event, which included many of the gay and lesbian leaders and artists of the day. Jim Pfaff took photos of the 1979 National March. From these photos, the following people have been identified as attending: Bill Spicer, Jane Levin, Jane Levin's partner, Kris Kleindienst, Brook Klehm and Lisa Wagaman. Bill has said that he rode with Rick Garcia. And of course, Jim Pfaff and Jim Thomas were there. There were quite a few others in these photos who have not yet been identified. Both lesbians and gay men were well represented at the March; gender parity being a strong value of the times.

|

| Some St. Louis Participants in the March on Washington. Photo by Jim Pfaff, © 1979 |

As it turned out, the National March was an empowering, transformative event for many of the people who attended it. In addition to Jane Levin and Jim Thomas, Bill Spicer and Jim Pfaff have spoken about this extensively in interviews. It was no surprise then, that given the highly successful March in October, 1979, members of the St. Louis Organizing Committee were energized to create an event in St. Louis modeled after the National March and to be held later in June around the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in 1969.

One fact about the St. Louis lesbian and gay community of 1979 is that there were more than a few organizations, clubs, churches, and student groups in various stages of formation, existence and dissoluton. Furthermore, many active individuals moved around in several groups and/or from group to group, exploring possibilities that their various social, political, religious and personal needs might be met. By the same token, it was equally possible that many of these people had never met each other, or only met in passing, so to speak. However, the subject of this article is tracing the evolution of the St. Louis Organizing Committee through several of the following years. The path which SLOC/Iris took is murky and dark, and fraught with peril, but with occasional patches of bright light.

As was characteristic of both the times and of the St. Louis LG community, heated discussions occurred between women and men, and stark differences emerged. A shaky generalization about this situation might be that on the one hand, most, but not all, gay men remained relatively unaware of and/or insensitive to the problems of women and lesbians—indeed, drag was often viewed as a parody of women outside of the gay male community and by some inside the community—while on the other hand, many, but not all lesbians, to be sure, were exausted from trying to build their own safe home within an essentially sexist and patriarchal culture (including a majority of the gay community), and had very little patience for bringing along the few gay men who included care and concern for lesbians within their own struggle. That said, those first months of 1980 when post-March on Washington SLOC was meeting to build a new organization and forge a new direction, gay men and lesbians struggled together for a time. One of the original members of the group, Jim Pfaff, has stated this description of those early group meetings of about 30 equally represented gay men and lesbians:

We met, and we met, and we talked, and we talked and we talked, and we talked. It was very politically correct. And we planned everything. We talked about procedures if people wanted to drop out, and how they needed to come and talk, whatever, it was all set up. Two of the women that were very active that I really liked, like they had other things that they wanted to do, and they dropped out, but they came to a meeting, we had a very good session.

Jim Pfaff also remembers that

I came up with 'Iris', somebody was wanting to name it “Lorena,” after Eleanor Roosevelt’s girlfriend. [I said] no, no that’s a little obscure, anyway, I came up with 'Iris', and Iris is the goddess of the rainbow. … And they liked the idea. And they kept, when they threw us out, they kept the name. That’s one of the things I have against them.

It is clear that this adoption of the name 'Iris' for the group was firmly in place by the Walk for Charity on April 20, 1980. In my own first person account of that day, I wrote "Women from Iris are doing a really fantastic job of getting the crowd to cheer. 'Two four, six, eight; being gay's as good as straight' rings out loud and clear."

A trail mark on the path of the evolution of SLOC/Iris can be seen in an article by Jim Thomas in the first issue of No Bad News. Thomas reports that about 30 women and men attended an informational meeting at MCC on May 12, 1980 describing the goals, structure, proposed projects, and historical genesis of a newly formed group, Iris. The St. Louis Organizing Committee, having helped to mobilize support for a march in St. Louis, continued to meet monthly throughout the early months of 1980 to discuss "the needs and concerns of the … community and appropriate structures to deal with them." The three stated major goals were political growth, education and media advocacy. General membership was to meet regularly, with a steering committee monitoring the work of any committees that formed.

It is clear that Thomas took a strong leadership role in Iris, and of course, in the community of the time at large. The August, 1980 issue of No Bad News credits Iris with conducting a poll in mid-July of political candidates for the Aug. 5 primary in Missouri. Only 3 of the candidates for state and federal offices responded. Thomas, speaking for Iris, while expressing disappointment, saw the advantage of this poll as educational, informing the candidates of the existence of a lesbian and gay constituency with specific concerns and interests. Also reported on in the same issue is a meeting of three members of the community with KMOX-TV representatives to discuss complaints about a CBS special entitled, "Gay Power, Gay Politics. While not specifically featured as an Iris event, Thomas, Bill Trotter and Laura Moeller were the community members who were involved. The meeting lasted three hours and covered a broad range of community concerns, which was seen as positive.

However, despite these outward appearances, all was not well within Iris. Two former members of Iris, Jim Pfaff and Thomas, have commented extensively on their ejection from the group. Pfaff, who did pour a lot of his energy into the formation of Iris, remains bitter about these events:

Well, we came in one night, and the women announced that it was going to be an all-women’s group. They didn’t say THEY were leaving; they kicked us out. That’s one of the reasons I’m so pissed. They had no position to do that, but, I remember [them saying that] there were things that they wanted to talk about that wouldn’t involve us, and one of ‘em said, well, rape, for instance. And I said, “Well, rape involves men, too.” And one of ‘em said, “You’re ripping us off.” [pause] I still would like to do violence. I would like to slap her. “You’re ripping us off.”

Thomas also confirms this event. Here is his poignant statement:

Iris had a strong lesbian feminist component. In fact, it fell apart over tensions between the men and the women. … In particular there was one really, really awful meeting where this discussion of rape came up, and several women said it was impossible for men to be raped. And that was kind of the beginning of the end. I actually walked out of that. ‘Cause I had been raped.

Thomas remembers that this event occurred "not a whole lot later" than the Celebration in April.

There are two sides to every story (at least), and as a sincere inquirer, I have had a lot of difficulty in accessing defenders of the other side of this one.

One source of information from a lesbian point of view about the differences between gay men and lesbians that were stewing and brewing around this time is the April, 1980 issue of Moonstorm: Lesbian Feminist Newsletter for Women. The newsletter presented three full pages of commentary on the issue. While no names are on the articles, it appears that one woman in the Moonstorm collective wrote three columns on lesbians working with gay men, while another woman in the collective wrote three columns on gay men working with lesbians.

The article on the lesbian point of view starts with the fact that two women had represented Moonstorm in the planning for the Celebration. The collective had discussed the matter of gay men and women working together. Most of the collective saw the need for a stronger gay presence in St. Louis in light of the emergence of stronger oppression. However, most were not disposed to work with gay men because they are sexist—meaning "that gay men are not (as a whole) aware of the oppression of women in this society. As men, gay men have a lot more privilege than lesbians." Some lesbians are aligned with the women's movement, which makes sense in light of the fact that lesbians experience discrimination both as women and as gay. The article cited men from the organization "Brothers in Change" as being aware that women are oppressed, and said most of the women felt good about that group. When women and men worked together against the Anita Bryant campaign in 1977, there were more lesbians than gay men involved. Now in the current working together, the ratio has reversed. "Our biggest dividing line seems to be that gay men like to be around and deal with men and lesbians like to socialize with and deal with women." The collective did not come up with any answers to problems, but did think that gay men should identify with a larger base of oppressed people.

The article on the gay male view was written by a member of the Moonstorm collective who was working on the Celebration Committee, and hence interacted with quite a few gay men. She initiated informal conversations with a few of the men, and set down main points of agreement or disagreement. She believed that the men in the Celebration Committee were representative of the gay male community at large. With a few exceptions, she found most of the men to have sexist attitudes. The men she spoke with agreed that lesbians were much more politically involved than a majority of gay men. Some of the gay men had problems in dealing with any women, not so for others, who felt close to women. Most of the men saw that their sexism came from the larger culture, and while they needed to be more willing to learn from women, the women need to be more willing to educate them. She also mentioned that a couple of the "Brothers for Change" men were more feminist. Some men suggested that more mixed social functions were needed, but acknowledged that communication problems exist. Others saw that there were two gay cultures, tied together by the bond of oppression, but separated by male privilege and different economic status, women being more "third world." Everyone saw the need for lesbians and gay men to work together, however. Finally, many men found problems with political groups themselves, poor leadership, poor understanding of how to work together, and women withdrawing, rather than being more confrontive about sexism.

These views from Moonstorm do not necessarily represent the specific beliefs or attitudes of the women who participated in and eventually took over Iris, but they do present a concrete background against which to understand the evolution of the group. The interview with Jim Pfaff also made clear that Jane Levin and her partner had left Iris "to pursue other objectives" before the split occurred, and that he only experienced unilateral action from some (unspecified) women in the group. Clearly, there is much that is still unknown about the dynamics of this particular group.

Suzanne Goell, founder and managing editor of No Bad News for its entire publication cycle has told me that she wrote all the copy for the first issue. She repeatedly attempted to print news of interest to the lesbian community in St. Louis, but found it hard to make contact. Post-split Iris, however, was highly critical of her newspaper, in general, for what they say is its "concentration on the male bar scene," and particular, for its running of the frankly gay male pornographic series, The Adventures of Lance Hardden. They state that "NO BAD NEWS so far has not evinced a quality that we can accept."

However, Goell was aware of these differences of opinion from the beginning. In her extensive report on the first pride activities she included this:

Despite the successes of the Celebration, the week was not without its problems. Many women expressed reservations about the male orientation, as well as the pricing of some events. Women were also disappointed in the lack of interest shown by men in activities sponsored by women's groups, most notably the open house at the Women's Eye Bookstore, which only two men reportedly attended.

The October, 1980 issue of No Bad News carried a letter from "The Former Members of IRIS," presumably the ones to whom the ultimatum about banning men from the group was issued. It is written in a completely positive tone, with no mention of the difficult final meeting. It sketches a background history of the group, and then announces this:

It is sufficient to say that the split was precipitated by the women of the group and was along gender lines. The basic feeling among the women was that their energy was being sapped by the men in disagreements over tactics and by the presence of sexism in the men. The women will continue as an all-woman group, keeping the name IRIS. The rest of us—all men at this time—have decided to continue as an open group, maintaining political and educational goals. We will choose a name soon.

In a long paragraph the men—hoping to avoid or minimize damage or infighting—give Iris their blessings and support in their decision, ask the community to support Iris too, and recognize that the "new Iris can be a positive and vital force for the benefit of us all." The men sketch their plans for the future, and concludes with a plea for greater understanding for community and individual needs.

The January, 1981 issue of No Bad News contained this letter to the editor:

Editors, NO BAD NEWS:

In the October issue you published a letter from the former members of IRIS. We are responding as present members of IRIS.

We appreciate the understanding of the men who wish us well. We feel the need for a separate group not in hostility to men, but in anticipation with working with a group of women that is thoroughly centered in the bonding of women. We feel energized by this political stance, and we encourage the support of IRIS by other women.

Thanks.

Others have said in interviews that Iris continued to work as a group and accomplish things after its becoming a women-only group. In doing research for another article, I scanned the titles of all the articles in No Bad News from its inception in June, 1980 to the final available issue in December, 1985. I did not see a single reference to the work of the organization Iris after 1981. This does not invalidate the claim of the continued existence and work of Iris. I can only hope to identify and interview one or more female members of the group who continued on.

And what of the men who continued to work together after being ejected from Iris? No clear answer is available at this writing. However, an interesting open letter appeared in the May, 1981 issue of No Bad News from the Officers of the Washington University Gay Community Alliance. Thomas was one of the four officers who signed the open letter, which explains changes in the group Concerned Lesbian and Gay Students. [Ed. note: This group had a major role, as CGS, Concerned Gay Students, in conducting the 1979 Celebration of Lesbian and Gay Pride held on the Washington University campus.] The letter explains three changes, the organizational name change to CGS from CLGS, the rewriting of the charter and bylaws, and the redirection of the group towards "the needs of gay men." The letter goes to some length to describe the group's careful consideration of the issues involved and concludes with this paragraph:

We firmly believe that this will result in a more resilient and active organization which is for the best of all of the Community. Many times, such splits have clearly sapped our energies to the loss of all. But we also believe that there may be times when such a split can be of positive value. We wish, in particular, to reassure our Lesbian sisters that our decision in no way lessens our commitment to justice for all segments of our community. We hope to maintain active communication and fully understand that many concerns of the Lesbian community should be and are our concerns as well.

It is not clear whether this change in the focus of CGS/CLGS/WUGCA is a point on the path from the evolution of SLOC/Iris, or whether the trail just became too dim. Perhaps the change of focus to the needs of gay men by the student organization can best be understood in light of a different, fascinating phenomenon. Perhaps the women's community was so well-organized and strong on the Washington University Campus of the late 1970's and early 1980's that there really was a need for a separate organization catering to the needs of gay men.

References

Andris, Jim, "Even Alexander the Great," No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 2.

Clendinen, D. and A. Nagourney, Out for Good: New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999, 716 pp.

Goell, Suzanne, "Re: LGBT History," e-mail to Jim Andris, May 21, 2013

Goell, Suzanne, "Celebration of Lesbian, Gay Pride is Successful Community Builder, No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 1, 8.

Interview of Jane Levin by Jim Andris, 12/16/2013.

Interview of Jim Pfaff by Jim Andris, 5/9/2013.

Interview of Jim Thomas by Jim Andris, 7/17/2012.

"Iris Polls Candidates, Collects Legislative Info.," No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 3, p. 3 (August, 1980)

"KMOX-TV Representatives Discuss Local Complaints," No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 3, p. 3 (August, 1980)

"An Open Letter," No Bad News, Vol. 2, No. 5 (May, 1981)

Thomas, Jim, "SLOC Impetus for Iris: St. Louis Activist Group for Lesbian, Gay Rights Founded," No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 1. (Jun, 1980)

The Former Members of IRIS, "An Open Letter to: The St. Louis L/G Community," No Bad News, Vol. 1, No. 5 (Oct, 1980)

Iris Letters to the Editor of No Bad News

Editors, NO BAD NEWS:

Your publication may fill a certain need in this community, but we are dismayed at the concentration on the male bar scene and your blatent bad taste in the series, The Adventures of Dick Hardden. We agree with the writer of the letter you ran in the November issue, that your paper is unacceptable. You have alienated responsible members of the gay community from reading and contributing to such a repository of trash.

You do not identify the varous sources of negative and favorable comments about this series. You need to acknowledge that your readers may include many who are not homosexual as well as those who are. It is irresponsible of you to imply that you are serving the special needs of gays, as opposed to heterosexuals, when you are actually serving up pornography for anyone who has the inclination to be titillated.

You claim committment to an improvement of the status of the area gay community, and we challenge you to clarify this. The community has some right to know the personal and political allegiances of editors who make such claims.

We, the members of IRIS, do not feel comfortable using such a publication as NO BAD NEWS for publicity or communication. We are oncerned about the quality of life for women, particularly lesbians, and NO BAD NEWS so far has not evinced a quality that we can accept.

We would welcome a forum where the views and insights of lesbians might be shared, but we see little hope that you can provide such a place. This is saddening.

In the interest of generating some useful response from other women who may still be reading your news (several we know have given up on it), you may use our letters as we are sending them, two separate letters.

The Members of IRIS

Part of the story of the 1979 origins and functioning of the St. Louis Organizing Committee (SLOC) has been told in another article on this website: National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, Oct. 14, 1979.